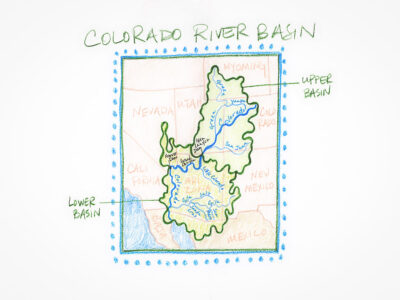

Our decisions really can have far-reaching impacts. Especially when they concern something as important as allocating the water supply for a region covering seven states.

The Colorado River Basin is in the midst of a drought that started 25 years ago. The river has lost 20% of its flow, and the states it serves are having to adjust their expectations for available water. In part, this is a natural drought cycle made worse by rising temperatures.

The root of the issue though is willfully poor decision making 100 years ago.

In January 1922, representatives of the seven Colorado River Basin states, collectively called the Colorado Compact Commission, met for the first time. Their task was to divide up the river’s water for future development. They had the findings of two different technical reports at their disposal.

One said the Colorado River had enough water for all of their plans — the other said it didn’t.

Water Supply Paper 395

Water Supply Paper 395 was authored by E.C. LaRue of the USGS.

“Our modern understanding of the Colorado River dates to the 1916 publication of Water Supply Paper 395 . . . the first comprehensive engineering report on the Colorado River Basin.”

~ Science Be Dammed

LaRue looked at Colorado River flows from 1899 – 1920. His paper included a full discussion of hydrological records, existing irrigation systems, potential reservoir sites, and possible irrigation areas. He estimated flows at multiple locations and analyzed the flows needed for irrigation.

The first stream gauges were installed on the river in 1900, but drought periods in the 1880s and 1890s were well known by that point. LaRue attempted to estimate those historical flows but noted that more work was needed on this.

LaRue’s conclusion: there was not enough water to fully develop the basin.

The Fall-Davis Report

The Fall-Davis report was authored by Arthur Powell Davis, director of what would become the Bureau of Reclamation. He also looked at flows from 1899 – 1920.

“While the Fall-Davis report would significantly advance the future development of the river, its treatment of the hydrology of the Colorado River was confusing.”

~ Science Be Dammed

Davis’s report contained two important tables that estimated flows at different locations, but he didn’t include any information on data sources or discussion of how the numbers were developed. Additionally, though it was a known issue, he never adjusted his tables to account for a decrease in flow due to upstream agricultural use.

The result is that his flow estimates were too high.

Davis’s conclusion: there was enough water for everything the states wanted to do.

Moving Forward

The states, set on securing water for all of their development plans, chose to use the Fall-Davis report as their primary source of information.

E.C. LaRue offered his expertise to help the Commission better understand the hydrology of the river, but they never asked.

Over the course of decades of meetings, the Commission chose to ignore the drought evidence and any suggestion that there might not be as much water as they thought.

“Before the Compact Commission even began its meetings, the path had been chosen. The optimism of Arthur Powell Davis and the Fall-Davis report, rather than the caution of E.C. LaRue, would guide the negotiations of the Colorado River Compact and become embedded in a century of development and conflict.”

~ Science Be Dammed

The states wanted what they wanted and failed to consider what the river could actually provide.

Today, the Colorado River Basin is experiencing one of those drought periods the Commission chose to ignore. And we now know the region has a history of extended droughts that dates back much further than the 1880s.

The source of the Colorado River’s troubles isn’t a lack of precipitation; it’s a lack of respect.

Sources:

- Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River, by Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

The Great Law of Peace

The Great Law of Peace